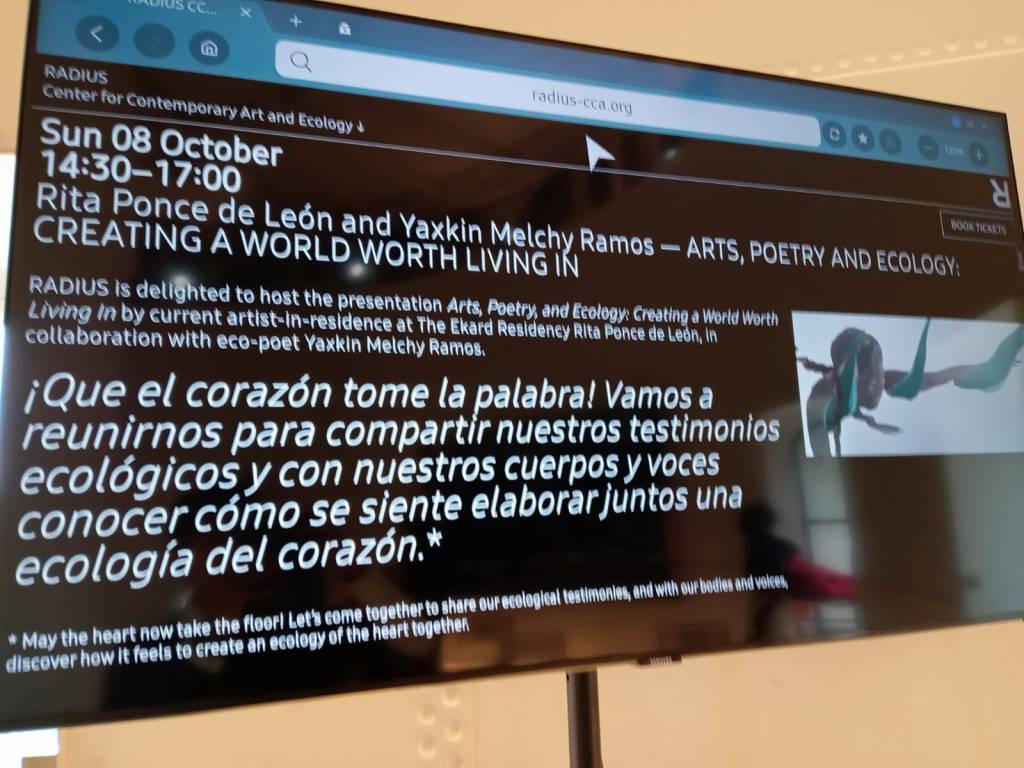

I was invited to Holland by my friend, the artist in residence Rita Ponce de León, and the Ekard artistic residence. We presented a talk with Rita at the RADIUS museum (in the city of Delft), a fascinating Museum of Art and Ecology built in what was once a water tower.

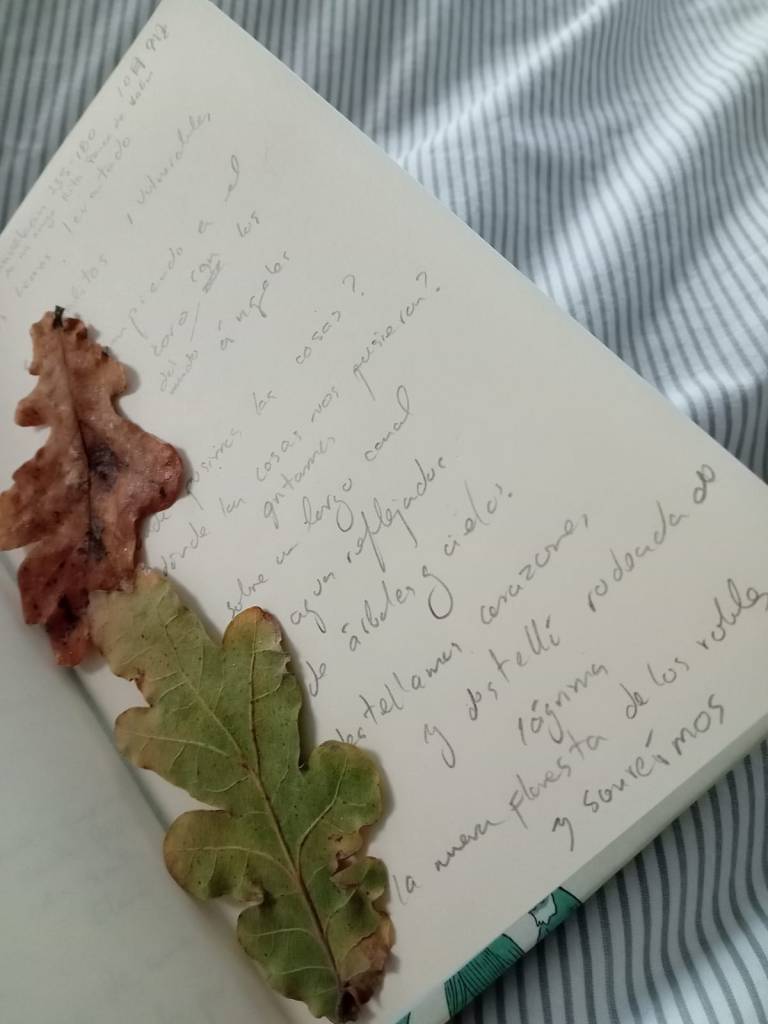

Although my trip to Holland was short, it was very significant since I lived in Leiden for three years as a primary school child. With Rita, we walked through the Meijendel dunes in Wassenaar and Leiden. When I arrived in Holland, I wondered what the ecopoetic meaning of this trip would be. In Meijendel, I realized something in my heart, so I took a fistful of sand and thanked the Dutch lands for the good memories from my childhood, memories of the countryside, the forest, the sea, the canals, and the flowers that made me happy and awakened in me a sense of nature’s beauty. With Rita, we went to my old condominium on Boerhavelaan Street, and we found the oak tree (zomereik) under which I used to play in the middle of the courtyard. Surprisingly, a swing is still under the leaves, meaning children are still visiting this tree. Under the zomereik, I said to Rita, isn’t our life short? With all its dramas, how is our life for a tree like this? For the oak, our life lasts a little longer than summer flies. And despite this, the tree offers itself generously and even feels admiration for our songs, just as we do for the song of the cicadas. Then I told the zomereik -dear oak, here I am back. I grew up and became a poet.

I remember Rita’s words during those days: “Recently, I have only seen comments from scientists who are very sad, angry, and worried about the climate crisis.” For some people, ecological concern makes them forget their love and gratitude for being part of the earth. With Rita, we discussed some ideas:

- Anger and worry are anti-ecological.

- There is nothing more ecological than gratitude and the feeling of fulfillment.

- Ecology is not only a program, an objective, a goal, or a horizon, but the consequence of a way of life. What would it be like to think ecologically from the patterns woven by experience?

- As my friend Pedro Favaron says, an indigenous ecopoetics is a way of life connected to the land and the sacred network of existence.

- Patterns woven by connected lives reveal the shapes of the heart’s learnings. Asian and Indigenous peoples’ thoughts and arts nourish our ecopoetics.

During the presentation at RADIUS, we made a small offering, discussed our work in synchrony (between the plastic arts and poetry), and led an «ecopoetic exercise» of memory and gratitude with the attendees.

Finally, I thank Renee and Bob, our hosts at the Ekard residence, Sanne Luteijn and Niekolaas Johannes Lekkerkerk, who managed the presentation at Radius, and photographers Newsha Tavakolian and Maarten Nauw for the photographs of this encounter with the lands of Holland. Also, thank you to Claire van den Donk for translating my poem into Dutch.

Wat doet een dichter?

(¿Qué hace un poeta?/What does a poet do?)

Hij verklaart de hemel met zijn zang

uit zijn bloed geboren

in eeuwige beweging

zijn bloed is het bloed van de rivieren

de ideeën in zijn geest

niet één valse schepping

want hij is zelf de schepping

het licht van de bladeren rakend

De sterren passen in de palm van zijn hand

zoals hij past in de handpalm van zijn broer

van zijn vriend, zijn metgezel,

van zijn geliefde

Zijn woord is er om

de moderne rook

die zich vastklampt en in onze harten nestelt

te verdrijven

Het lied van de dichter blaast

en waait het stof op,

troebleert de zeeën

met roerende rust

laat de keien lachen

de vogels verfijnen hun lied,

rivieren vloeien samen door hun zang

als kinderen die van dezelfde vruchten eten

Met zijn poëzie weeft hij

iets lumineus en schoons

dat in een oogwenk wordt verspreid

en de ochtenden van de wereld

bedekt met een zonnedauw

alle ochtenden van de nieuwe wereld

Hij deinst terug

voor de schitterende fascinatie

van zijn literaire vaders

hij laat de mantel van fascinatie achter

hangend aan een kapstok

en gaat naakt, ongekleed

met het lied van zijn haarstrengen

die onderweg vallen

op zijn kussen

op de badkamervloer

op de aarde van de buurt

op de bron waar hij zijn hoofd in onderdompelde

zoals de universiteit

waar hij zijn tijd bakkeleiend doorbracht

met onnozelen

dezelfde universiteit

waar hij ’s middags

de heldere spiegel van woorden bestudeerd

(een helderheid diepzinnig maar ook verontrustend)

Hij verliest strengen haar terwijl hij leest

wanneer hij zingt

als hij halthoudt om te luisteren

wanneer hij zijn broeders over het leven leert

terwijl hij deze zintuigen verliest

en zijn ogen en oren en zijn andere ogen

die nog steeds ruimte voor trots bewaren

en zijn nagels en zijn huid

en zijn botten

Hij heeft de hunkering naar het creëren achtergelaten

maar zijn ziel gaat voort, gezuiverd nu,

tot in de eeuwigheid.

Dan wordt er nog een dichter geboren:

— … Waar de oude meester ooit woonde

staat nu een boom.

San José, Pucallpa, 2016.

Ciudad de México, 2018.

Tsukuba, 2020.

Vertaald door Claire van den Donk, ARTDOK Research & Translations

Fui invitado a Holanda, por mi amiga la artista en residencia Rita Ponce de León y la residencia artística Ekard. Con Rita presentamos una plática en el museo RADIUS (en la ciudad de Delft), un fascinante museo de arte y ecología construido en lo que fue una torre de agua.

Aunque mi viaje a Holanda fue corto, fue muy significativo, pues yo viví tres años en Leiden cuando era un niño de primaria. Con Rita paseamos por las dunas de Meijendel, en Wassenar, y por Leiden. Cuando llegué a Holanda, me preguntaba cuál sería el sentido ecopoético de este viaje. En Meijendel me di cuenta de algo en mi corazón, tomé un puño de arena y le agradecí a las tierras holandesas por los buenos recuerdos de mi niñez, el campo, el bosque, el mar, los canales y las flores que hicieron felices mis días y despertaron en mí un sentido de la belleza de la naturaleza. Junto con Rita fuimos al antiguo condominio de la calle Boerhavelaan y encontramos, en medio del patio, el roble (zomereik) bajo el que solía jugar. Sorprendentemente todavía se encuentra un columpio debajo de su fronda, lo que significa que hay niños que visitan a este árbol. Bajo el zomereik le dije a Rita: ¿no es corta nuestra vida? Con todos sus dramas, ¿cómo es nuestra vida para un árbol como éste? Para el roble, nuestra vida dura un poco más que las mosquitas del verano. Y a pesar de ello, el árbol se ofrece generosamente y hasta siente admiración por nuestros cantos, tal como nosotros sentimos admiración por el canto de las cigarras. Luego le dije al zomereik — querido roble, aquí estoy de regreso, crecí y me volví poeta.

Recuerdo unas palabras que me compartió Rita hace unos días: “Recientemente sólo he visto comentarios de científicos muy tristes, enojados y preocupados por la crisis climática.” Para algunas personas, la preocupación ecológica les hace olvidar el amor y la gratitud por formar parte de la tierra. Con Rita conversamos algunas ideas:

- El enojo y la preocupación son antiecológicos.

- No hay nada más ecológico que el agradecimiento y el sentimiento de plenitud.

- Lo ecológico no es un programa, un objetivo, una meta ni un horizonte, sino la consecuencia de una forma de vida.

- ¿Cómo sería pensar lo ecológico desde los patrones entretejidos por la experiencia?

- Una forma de vida en relación con la tierra y la red sagrada de la existencia es, como dice mi amigo Pedro Favaron, una ecopoética indígena.

- Los diseños entretejidos por las vidas que se conectan nos muestran las formas del aprendizaje con el corazón. Del pensamiento y las artes de Asia, y de los pueblos indígenas, se nutre nuestra ecopoética.

Durante la presentación en RADIUS hicimos una pequeña ofrenda, hablamos de nuestros trabajos en sincronía (entre las artes plásticas y la poesía) e hicimos un ejercicio ecopoético de memoria y agradecimiento con los asistentes.

Por último, agradezco a Renee y Bob, nuestros anfitriones de la residencia Ekard, a Sanne Luteijn y Niekolaas Johannes Lekkerkerk, que gestionaron la presentación en Radius, y a los fotógrafos Newsha Tavakolian y Maarten Nauw por crear un registro fotográfico de este encuentro con las tierras de Holanda. También a Claire van den Donk por la traducción de mi poema al holandés.